How will the “Age of Oil” end?

2 Apr

With a whimper, not a bang. But the beginning of the end may not be that far away…

Countless times the end of the “Age of Oil” has been forecasted. All of these forecasts were wrong so far. But that does not mean that they will always be wrong in the future as well. The more spectacular forecasts of peak oil concentrate on diminishing supply. “Oil running out” in everyday terms. This has always seemed unlikely. Physical oil supply of course has some (unknown) upper limits. But that limit is far, far larger than any likely cumulative demand for the next several hundred years. If you allow markets to work, then the price will rise high enough so that enough supply will come forward. In market economies things don’t just run out.

Dawn of a new age – but not because oil will run out

Useful stuff, at a high price…

In the past 10-15 years this is indeed what has been happening: oil prices increased from around $20/bbl in today’s money in the ‘90s to above $100/bbl in the past few years. Oil demand has increased, and the last barrel of oil (marginal oil) is more expensive to produce. This is what is reflected in the price. The fact that oil demand is still increasing at the current price level is a testimony to the incredible usefulness and versatility of the stuff. And by the way, this higher price acts as a tax on the global economy: the world spends about 4% of global GDP on oil at an average oil price of $100/bbl. That spending would be only about 1% if oil prices were $25/bbl or if we used natural gas instead of oil – all other things being equal, i.e. disregarding the fact that cheaper energy would result in a more energy-intensive economy. This is one of the reasons why global economic growth is weaker than it would be, had the oil price stayed as low as in the ‘90s.

Gas is cheaper than oil everywhere, and will stay that way

Sources: BP, Bloomberg, own calculations

A more plausible script for the end of the “Age of Oil” goes like this: sustained high oil prices encourage technological development and substitution with other sources of energy on the demand side. After a certain time, there is a breakthrough in technology, and oil is no longer needed. This has already been going on to some extent as well – internal combustion engines have become more fuel efficient, for example. But note that high prices encourage innovation on the supply side as well. And so far we had more breakthroughs there: new technology has increased the (unconventional) oil supply – and that prolongs the Age of Oil.

Looking for the next killer app

So what are the future prospects of replacing oil with something else? In most stationary applications, there are cheaper alternatives to oil, most notably natural gas. And that substitution has been going on for a while – in rich countries for example there is hardly any electricity produced from oil (except for emergency cases like the period following the Fukushima disaster in Japan). The availability of natural gas depends on expensive infrastructure build-up, but this is going to happen in most places. Renewables, especially solar, will become cheaper as well.

The main question for the end of the Age of Oil is transportation. Here it seems to be difficult to replace oil. There seem to be three possible alternatives to oil at the moment: natural gas, hydrogen, or electricity stored in batteries. Biofuels are expensive and their volume is unlikely to be enough for a complete replacement even if they become cheaper. Future unexpected inventions may widen this list, but currently there are no signs of safe micro nuclear reactors or the existence of cold fusion or anything else that would be capable of replacing oil in mobile applications at a reasonable cost.

Natural gas: cheap, but unsexy

Natural gas propulsion is a tested and tried technology. It is possible to use natural gas in internal combustion engines, with little modification. It is also cleaner in terms of local emissions, and usually cheaper. The disadvantage is that higher volumes of fuel need to be stored onboard, and that the fuel distribution network has not yet been built up. The disadvantages make natural gas transportation face a “chicken and egg” problem in most places, although in freight transportation gas has already been spreading in the US and China.

If there is going to be cheap natural gas available in most places permanently, then its use in transportation may gradually spread – a “creeping revolution” instead of a breakthrough. But currently neither car manufacturers nor governments treat it as a priority – both of them view electric propulsion as the future of transportation. There is a general impression that electric cars are just around the corner, and it is not worth switching to natural gas cars en masse for a short period.

Natural gas cars are cheaper than electric ones

Note: Purchase price is the German retail price of the basic VW Golf variety with the given fuel. Lifetime fuel costs assumer 15K km use per year for 20 years, 50% higher fuel consumption than manufacturer data, except for electric where we assumed 20% higher. Fuel prices are recent retail prices in Germany. A 5% real discount rate was assumed.

There are few natural gas car models available, and market players are reluctant to invest in boosting the refueling infrastructure, given the low number of users. The EU is pushing for a wider availability of natural gas refueling stations, and we would not rule out natural gas eventually taking the place of oil, especially if there is a cheap way discovered that turns it into a liquid fuel that can be distributed in the existing infrastructure (currently this is expensive). But without CO2 capture natural gas is not a long-term solution.

Hydrogen propulsion in transportation seems to be an even less likely replacement of oil – although Toyota is promising a breakthrough in fuel cell costs, and that may change the outlook. In any case, fuel cells at the moment are most likely to be using natural gas or hydrogen derived from natural gas, so they may be a variation of natural gas drive. Cheap hydrogen from renewable sources or nuclear reactors, which do not emit CO2, seems to be far away at the moment. That leaves electric batteries as the most likely candidate to replace oil, at least as things now stand.

Electric batteries: huge cost declines needed…

There are many problems with batteries at the moment (recharging times, safety, durability, recharging infrastructure, etc.) but the most important is cost. Batteries are hugely expensive at the moment, and that is why car makers usually build in only a small battery that is enough only for a limited range, resulting in an inferior product. The cost of batteries is something of an industry secret. However, we can make a pretty good guess from the high price of electric cars. Estimates regarding current battery costs range from $250-500/KWh. The higher numbers are actually more likely.

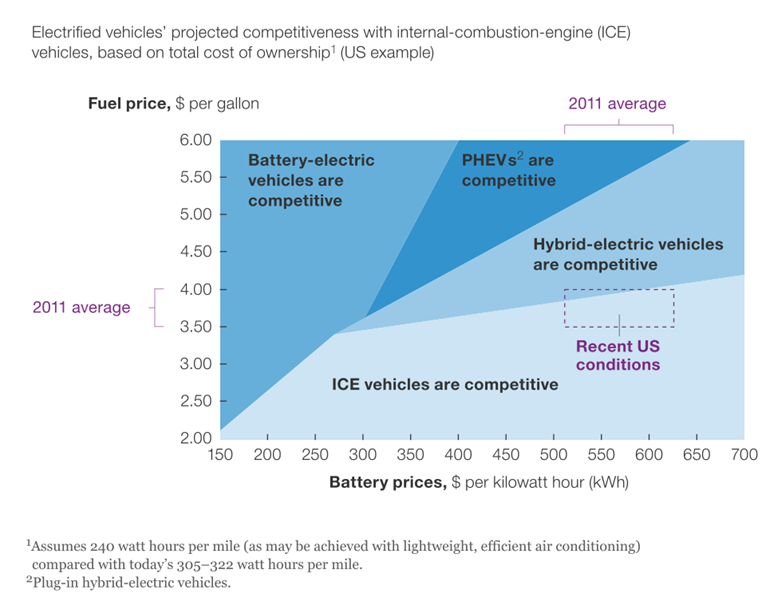

The following chart from McKinsey shows under what fuel and battery price assumptions electric cars would become competitive. Looking at the chart, we may not be that far from a breakthrough: fuel costs in Europe are well above $6/gallon, so look at the top of the chart. Plug-in hybrids should already be competitive in Europe, and full electric cars could soon be, if battery costs decline to around $350/KWh.

However, consultants are usually biased in favor of change. They used total ownership costs over the lifetime of the car, and probably low discount rates. Consumers also look at the sticker price. For an electric car to become a killer application, it needs to be relatively cheap to buy, and cheap to run, otherwise consumers would not put up with the risks and limitations of a new technology. To give you a better handle, at $350/KWh battery prices, a 500 km range car would need a battery costing about $26,000, or €19,000. That is more than the full cost of most cars. We think the price of this battery should be around $7-8,000 in order to become a killer application; when electric car prices are reasonable, consumers will want the stuff badly, and push for more recharging infrastructure and all the other necessary preconditions.

…but they may be coming

Battery prices have probably been declining by about 15% annually in the past few years. This is somewhat faster than previous estimates. Going forward, prices are likely to decrease by something like 10% (low hanging fruits-effect). This also seems to be the industry consensus. So let’s assume an annual decline of 10% in battery prices. When would we get to the killer app stage? The following chart suggests that by around 2030. However, the supporting infrastructure may not be completely ready by that time for a rapid roll-out, so 2030 is probably just the earliest date for the start of rapid replacement of ICEs. Replacement itself would take about 15-20 years globally (but potentially sooner in environmentally-conscious rich countries). This seems far away, but these dates are actually not that distant in an industry where investments have a long time horizon.

Source: own calculations

So based on this, the complete end of the Age of Oil is unlikely to come in the next 20 years at best. But oil consumption may be dented before that: in niche applications like expensive sports cars (Tesla) electric cars are already gaining ground. Plug-in hybrids, which have a smaller battery (see box for definitions) may become viable earlier than full electric cars, and “range anxiety” is not an issue with them.

Hybrids: cars that have a small battery, but it is charged from the braking energy and/or internal combustion engine (ICE). You can think of them as a more efficient ICE – no outside electricity is used. Example: Toyota Prius.

Plug-in hybrids: their (relatively small) battery can be charged from the outside. This may be enough for the daily commute and short trips (30-50 km range), but for longer trips there is the traditional ICE. The disadvantage is that you need to have a dual system. Example: GM Volt/Opel Ampera, but many more are coming/available.

Full electric cars: These don’t have an ICE, and thus have to rely on the electric recharging infrastructure. Examples: Tesla, Nissan Leaf.

Fuel cells: These devices produce electricity from hydrogen, but can be run on natural gas or even gasoline with a reformer that produces hydrogen from these fuels. Fuel cells can be very efficient compared to ICEs, but currently they are expensive. Also, the hydrogen refueling infrastructure is practically non-existent at the moment. No commercial fuel cell cars are available, though several car companies are promising this by 2015.

May oil NOT be replaced?

All this leads to the question whether oil will be replaced at all in the foreseeable future. We are big believers in price signals, and if the oil price stays around current levels, an eventual replacement is very likely. Oil may be replaced by cheap oil, if technological development in oil production makes it possible. If oil stays expensive, then even if for some reason batteries cannot become significantly cheaper, cheap natural gas in some form – or some other propulsion – is likely to replace oil eventually. Existing infrastructure and improving internal combustion engines are powerful conserving forces. But price signals are like water: eventually they will find a way. It may take decades, but here is a bet: young people today will likely to see the end of the “Age of Oil” – but this end is likely to be so gradual that historians will have big debates about dating it…

If you liked the post, follow Barrelperday on Facebook!

Or subscribe to our Twitter feed or Newsletter

very interesting article however it under plays the very promising research into high tech battery devices offering 500 miles per charge.

if this technology makes it to market it will be good bye to the internal combustion engine electric cars are vastly more efficient than I.C.E and far greener allowing for green electricity.

Only the power of the oil companies will keep this tech away from the public.

John, thanks for the reply.

10% annual cost decline in battery prices is not exactly downplaying. But you are right, there might be an even faster price decline, which would bring forward the switch.

However, we don’t believe in ‘oil companies killing the new technology’. They are occupied with other things (see e.g. our post Swimming naked, oil market edition). Oil companies are sometimes regarded as omnipotent, but they are not (see BP’s huge Deepwater Horizon fine). And even if they wanted to ‘keep it away from the public’, they could not determine which strand(s) of research could be a breakthrough (or breakthroughs), and there are way too many to control.