Oil can(’t) buy me love?

30 Oct

Thanks to their high per capita oil revenues, certain Middle Eastern countries were able to evade the Arab Spring through higher social spending – so far, that is. But with both break-even oil prices and geopolitical tensions on the rise, simply buying the silence of their citizens with generous hand-outs won’t work on the long run. The same holds true for Russia, where the petrodollar buffer will run out over the next 3-4 years.

What do you do when you are the leader of a not-so-democratic Middle Eastern country, facing a tide of popular unrest and the winds of change of the Arab Spring? You can choose to fight your own population, but that could perhaps lead to diplomatic isolation abroad. No more shopping trips to Paris? How awful! You can choose to bribe your population with promises of welfare spending, social hand-outs, education reform, health care benefits, and the like – if you have the money. Or you can choose to give in to public pressure and step down, paving the way for a regime change – but you are not serious, are you?

The need to placate the unruly masses underlines the J-curve theory, a term first coined by the American sociologist James Chowning Davies. Davies claimed revolutions tend to occur when a long period of growth is followed by a sudden reversal of fortune and prosperity. Although most Middle Eastern economies were not growing at double-digit rates prior to 2008, the global economic crisis plunged several of them into recession. This was accompanied by a drastic rise in food prices. In certain countries where the average consumer could not be compensated for this change by governmental hand-outs, the risk of social unrest did indeed increase dramatically. And history has proven time and time again that a combination of democratic deficit, bad government and socioeconomic hardship does not bode well for stability…

Almost two years on since the start of the Arab Spring, the picture is mixed. Regime change has already occurred in some countries, either by relatively peaceful means (Tunisia, Egypt) or by military confrontation (Libya). Syria is in a state of civil war, but is likely to eventually undergo some form of regime change. The key question of how the events unfold in each country depends on several factors (ethnic and religious composition, strength of the opposition, international pressure, size and might of the military, regional spillovers, etc.), but one important aspect is the role of oil revenues in shaping the politics of these Middle Eastern countries.

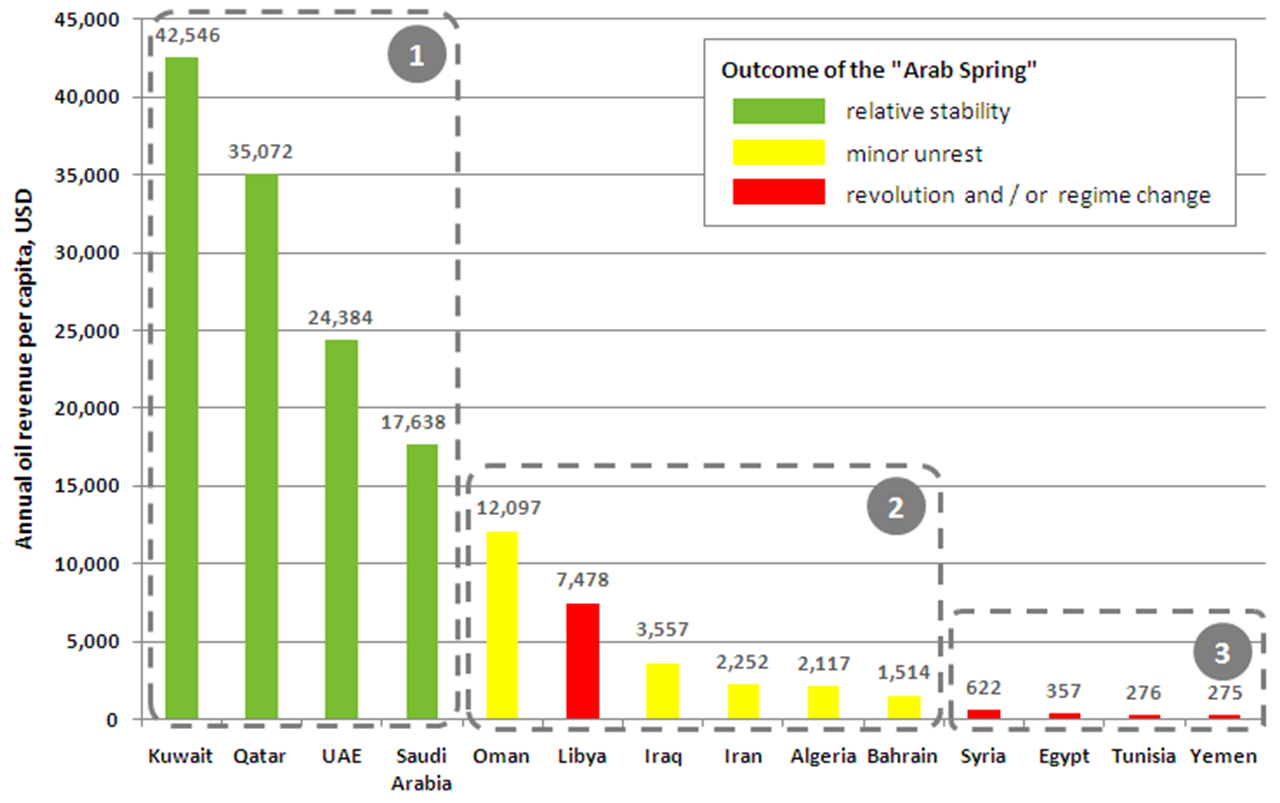

Everyone knows most Middle Eastern countries are awash with oil, but the degree to which this affects economic and social policy varies by country. In this regard, it is not (necessarily) the total amount of hydrocarbon reserves or the level of daily production that matters most. Instead, it is particularly telling to assess per capita oil revenues, in light of the outcome of the Arab Spring in each country.

The oil revenue ladder

Source: own calculations, CIA World Factbook

Note: Oil price of USD 115 used for calculations.

The lucky ones

Countries in Group 1 (Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia) are all characterized by vast hydrocarbon reserves, large-scale production and an economy intrinsically dependent on oil and gas revenues. These countries were able to avert social unrest and calls for political change during the Arab Spring thanks to their increasing levels of per capita oil revenues. Take the case of Saudi Arabia, for example, where an estimated 80% of government revenue originates from the petroleum sector, and where government spending has increased by 54% since 2008 – and the country can still avoid a budget deficit. Saudi Arabia approved a USD 180 bn spending plan for the current fiscal year, which included substantially greater expenditure for social and educational programs, welfare packages, energy subsidies, etc.

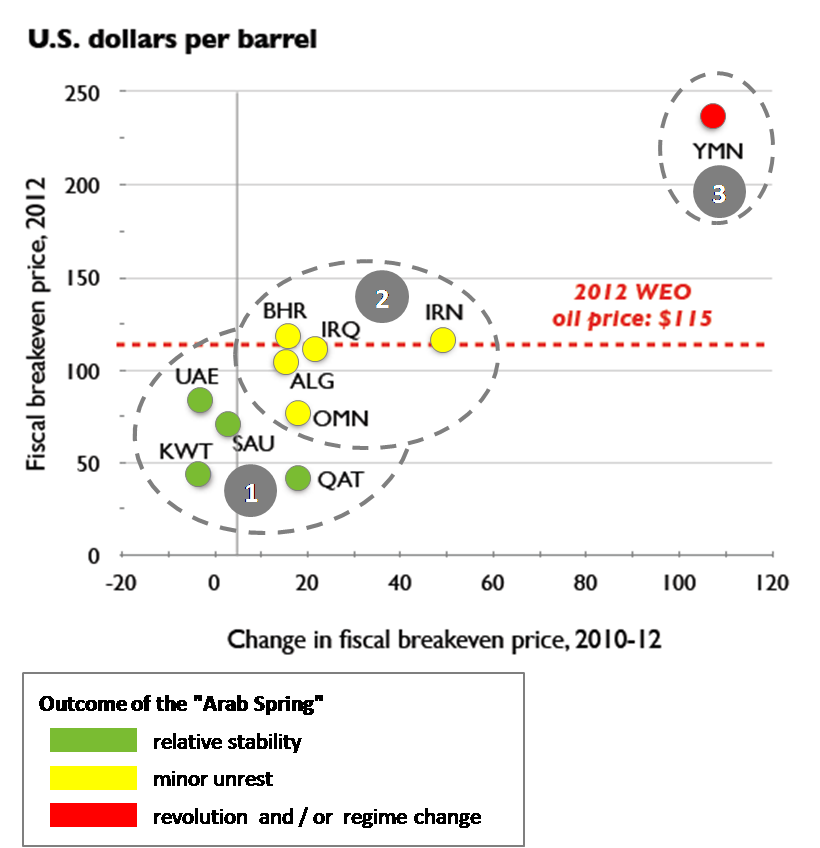

Higher levels of spending inevitably raise the so-called break-even oil price, meaning the amount per barrel (generally in US dollars) that is required for an oil producing country to balance its fiscal budget. In fact, the break-even oil price has already been on the rise in a number of Middle Eastern oil exporters over recent years. Such large-scale and excessive spending can lead to a dangerous vulnerability to oil price fluctuations.

Break-even prices have been rising

Source: IMF “Middle East and Central Asia Regional Economic Outlook Update”, April 2012

But simply bribing the population to buy its silence and tranquility is a losing game: you need to continuously increase living standards to maintain social peace. And oil prices will not rise forever to provide revenues for that. This is especially problematic in the case of Saudi Arabia, where dynamic population growth and high inflation are already weighing down on the economy.

Nowhere to hide

In Group 2 countries, per capita oil revenues were not high enough for them to afford fiscal expansion as a means to calm their populations. In their cases, the Arab Spring generally led to minor unrest, although the case of the Libyan revolution proves an exception to this rule. Libya’s case raised eyebrows in many of the more oil-rich states, because prior to the system’s collapse many had thought that Libya had enough oil revenues to avert it.

Finally, it seems no wonder that Group 3 countries, with the lowest levels of per capita oil revenues in the region, were faced with violent uprisings and the threat of civil war. While the outcome of fighting in Syria remains unclear, Tunisia, Egypt and Yemen all underwent a regime change over the last two years.

Russian reckoning

This is not just a Middle Eastern phenomenon – Russia is facing the same problem. With oil and gas revenues accounting for approx. 10% of the GDP in 2011, the economic model of the Putin (and Medvedev) era was to ensure high spending buttressed by petroleum revenues. Such spending sprees helped President Putin weather out recent protests against his rule, and even to win elections this spring. In fact, he made several ostentatious promises on the campaign trail (such as increased public sector pay, higher social benefits, regional development funds, boosting pensions, modernizing the armed forces, etc.). Although the current account benefitted from high oil prices in 2012, it remains vulnerable to price shocks. In fact, the petrodollar surplus could disappear by 2015, and the IMF forecasts that 2016 would be the first year of Russia running a deficit. Meanwhile, even the most optimistic Russian budgetary forecasts envision only a gradual decrease in the break-even price, from the current USD 116 to USD 104 in 2015. Therefore, the removal of the petrodollar buffer could potentially force the Russian government to introduce presumably unpopular reforms.

Overall, it seems that while high per capita oil revenues may provide some room for maneuver in times of unrest, rising break-even prices, overstretched budgets and irresponsible campaign promises may not be able to stave off uprisings indefinitely. But whether a politician is more interested in the long-term economic feasibility of his / her policies than in short-term political survival is another story altogether.

If you liked the post, follow Barrelperday on Facebook!

Or subscribe to our Twitter feed or Newsletter

Tags: geopolitics, MidEast, oil

No comments yet