Just divorced: Sudan, South Sudan and oil

5 Oct

The national anthem of South Sudan (chosen in a televised competition in 2010) calls upon the “land of great abundance to uphold us united in peace and harmony”. Let’s be polite and say that this is more of an aspiration than reflecting current realities.

Subscribe to our newsletter to get instant alerts of our new posts!

By Diána Szőke

Many developing countries in Africa would balk at the good fortune of having over 3 billion barrels of proved oil reserves under their feet (its value at current prices is around USD 400 billion). In this respect, South Sudan is indeed blessed. However, a year after gaining independence from Sudan, it is unable to reap the benefits of its abundant petroleum resources, partly as a result of ongoing disputes with the north. Its oil production remains shut in. The case of South Sudan illustrates how a lack of available infrastructure can cripple a highly promising oil industry, as well as how mineral fortunes are a mixed blessing, especially if your institutions are somewhat less developed than those of, say, Norway.

Source: CIA World Factbook

South Sudan does indeed have much potential: slightly larger than France, with just around 10 million people, it is comprised of grasslands and rare tropical forests. It has plenty of natural resources of minerals, hydropower and – predominantly – petroleum. South Sudan boasts one of Africa’s richest agricultural areas, whose fertile soils feed roughly twice as many cattle as people, and it has no external debt.

While this great abundance does exist, peace, harmony (and economic growth) are lacking. South Sudan is one of the world’s poorest countries; most of its citizens depend on subsistence agriculture just to get by, and half the population relies on food aid. Its industry and infrastructure are severely underdeveloped: according to the latest figures, the country has just 60 km of paved roads. Electricity can only be produced by expensive diesel generators, while running water is scarce. Despite vast petroleum reserves, South Sudan remains wholly reliant on imports, and is plagued by high fuel prices. Its people live in abject poverty, with literacy rates around 30% of the total population. (Incidentally, there are no official figures on the size of this population, since no comprehensive census has been carried out in decades.) According to the UN, a 15-year-old girl in South Sudan is likelier to die of childbirth than she is of finishing school.

So why is South Sudan failing to live up to its potential? The answer lies in a history of conflict. Sudan, Africa’s largest country at the time, became independent from joint British-Egyptian rule in 1956. Since then, it was embroiled in Africa’s longest-running civil war between the majority-Arab Muslim north and the Christian-animist south, resulting in the death of approx. 2.5 million people because of fighting, starvation and drought. An accord signed by the parties in 2005 created a fragile peace, punctured by sporadic bouts of clashes over ethnic identity, grazing rights, and the territorial sovereignty of oil-rich regions. In January of last year, an overwhelming majority (98%) of South Sudanese voted in favor of secession, and the country became formally independent on 9 July 2011.

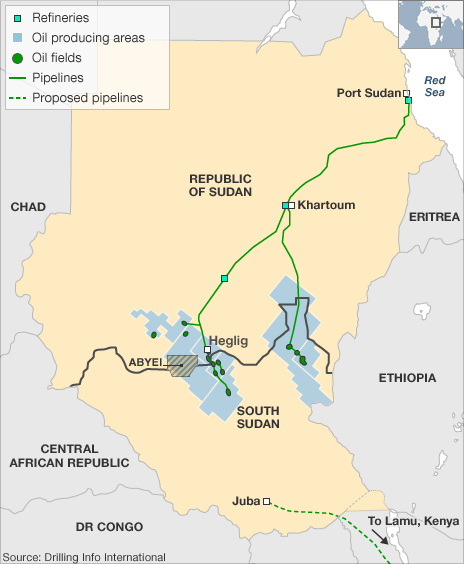

Many saw independence as a possible turning point for South Sudan, thanks in part to its huge petroleum reserves. Sadly, its oil wealth has proved more of a curse than a blessing, so far (as in several other African countries). Although South Sudan inherited the bulk (around 75%) of Sudan’s oil reserves, the only two pipelines connecting the oilfields to refineries and shipping facilities at Port Sudan on the Red Sea remain in rump Sudan. To put it crudely: Sudan has the infrastructure, while South Sudan the stuff to fill it with. This puts South Sudan in a precarious position, since oil accounts for nearly 98% of its budget revenues. A potential fallout of production from South Sudan makes Sudan vulnerable as well, as it does not get to collect transit fees.

After years of tensions between the two sides on oil-related issues, talks on the sharing of oil revenues and transhipment fees broke down in January this year, resulting in the temporary shutdown of South Sudan’s oil production (approx. 500 thboepd, or about 0.5% of the global total), production still has not resumed. This amount does not seem much in the global context, but in the world of relatively tight oil markets this added to the upward price pressures. The move crippled the interdependent economies, and South Sudan was quickly faced with the threat of bankruptcy. It was forced to halve all public spending (except for salaries).

Source: BBC News

In April 2012 the two countries almost went to war, and only growing international pressure and the fear of UN sanctions brought the two sides to the negotiation table. In August, they agreed that South Sudan will pay Sudan a lump sum of USD 3 billion as “compensation”, while transit fees will be waived for a period of 3 years. A deal was signed on 26 September, setting forth the resumption of oil exports from South Sudan and the demilitarization of certain contentious border zones.

The usual wishful thinking mode set in, and the deal was heralded by the media as yet another diplomatic breakthrough. But it is much too soon to speak of any victory. A number of vital issues remain unresolved, such as the territorial sovereignty of the oil-rich town of Abyei, or the status of the major Heglig oilfield. The conflict is further exacerbated by disputes over cattle grazing, ethnic clashes, and the presence of hundreds of thousands of refugees and internally displaced persons in the border area. In this regard, oil only complicates matters: it is much too attractive a commodity, and neither side is willing to make any concessions on its ownership – if for nothing else, then for the fear of the other side becoming decisively stronger.

In fact, reports suggest the conflict may be turning into a proxy war. Iran is standing by Sudan, with Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad claiming his country and Sudan are both victims of “arrogant powers and enemies of mankind”. Meanwhile, South Sudan is receiving military assistance from Israel. China is also heavily invested in both countries, and even offered to buy oil at above-market rates in February.

In the long run, whether or not the abundance of petroleum will help keep South Sudan together and complement its economic development is yet to be seen. One hope is that it could build a pipeline to Lamu in Kenya and thus circumvent its arch enemy. Failing that, the cycles of brinkmanship and reconciliation between Sudan and South Sudan are likely to continue. It seems oil is not always a blessing…

If you liked the post, follow Barrelperday on Facebook!

Or subscribe to our Twitter feed or Newsletter

No comments yet